Using Recurrent NNs and Keras to Reproduce the Input-Output Behaviour of a State-Space Model of a Dynamical System

Before we start (for impatient): the codes used in this project are posted here.

This post is motivated by an interesting question posted on the Keras Github page. The post in which the question is stated starts as follows: “For a final thesis I am working with Keras on Tensorflow and have to investigate how LSTM Networks can be used to identify dynamical systems.”

Feedforward neural networks have been extensively used for system identification of nonlinear dynamical systems and state-space models. However, it is interesting to investigate the potential of different recurrent neural network architectures for the identification of state-space models. In this post, I will report my progress on this interesting topics and I will post codes and my thoughts. The complete code can be found here.

So let us start with a problem definition. So let us start with a problem definition. Various dynamical systems, such as robotic arms, oscillators, and even economic systems, can be mathematically described by a linearized state-space model having the following form:

where $\mathbf{x}\in \mathbb{R}^{n}$ is the state vector, $\mathbf{u}\in \mathbb{R}^{m}$ is the input vector, and $\mathbf{y}\in \mathbb{R}^{r}$ is an output vector. The matrices $A\in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}$, $B\in \mathbb{R}^{n\times m}$, $\mathbf{C}\in \mathbb{R}^{r \times n}$ and $D\in \mathbb{R}^{r\times m}$ are the system matrices.

The vector $\mathbf{u}$ represents external influences on the system. The vector $\mathbf{y}$ is the vector of the observed variables, and the vector $\mathbf{x}$ is the state vector. Loosely speaking, this vector represents the internal system memory.

The identification problem for the system \eqref{eq1:state}-\eqref{eq1:output}. Given the sequence of the input-output data , where $N$ is the length of the sequence, estimate the system matrices $A$, $B$, $C$, and $D$ up to (unknown) similarity transformation. The estimated state-space model should accurately reproduce the input-output behavior of the original system.

From a practical point of view, it is easier to estimate a discrete-time version of the original system. The discrete-time system has the following form:

where $k$ is the discrete time instant. That is, the state and other vectors are approximations of the original state at the time $t=kT$, where $T$ is a sampling period.

Obviously, the recurrent neural network architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory networks do not have the exact structure of the state-space model. However, we can still employ them to learn to reproduce the input-outpur behavior of the discrete-time state-space model \eqref{eq1:stateDiscrete}-\eqref{eq1:outputDiscrete}. That is, when we apply the sequence of inputs to the neural network, it should produce the sequence of outputs that accurately approximates the output sequence of the real-system.

In the sequel, we will show how to perform this using the Keras machine learning toolbox. For presentation clarity, this will be explained using the example of a mass-spring system.

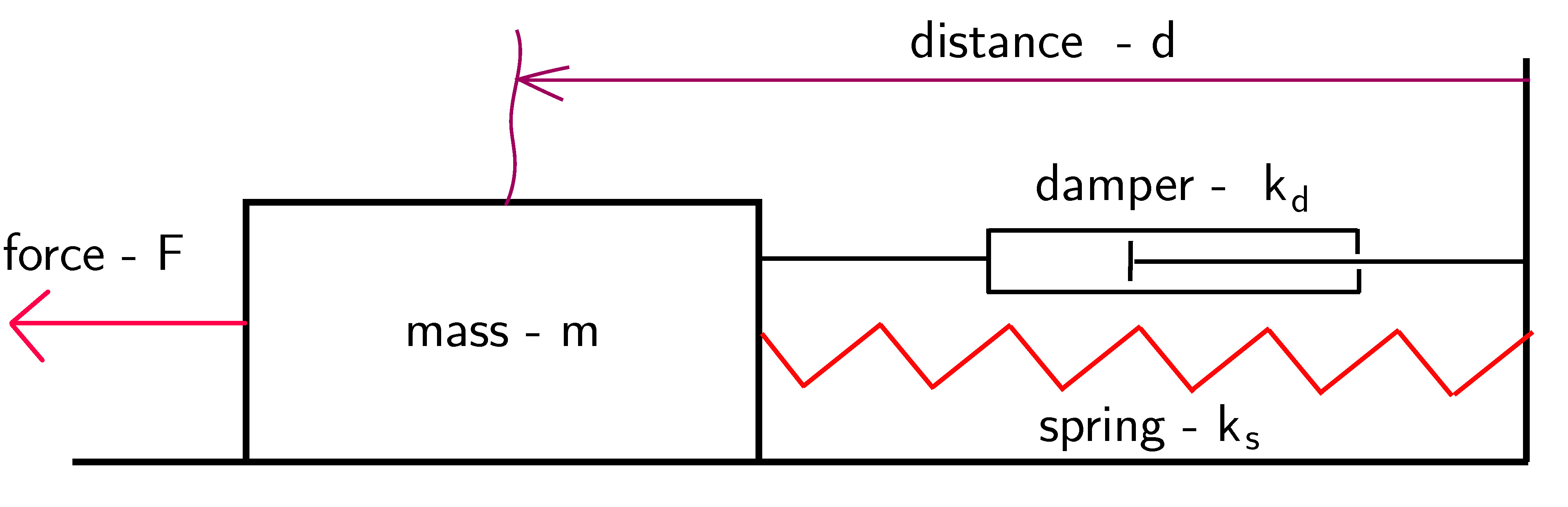

The mass-spring system is shown in Fig. 1.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Mass spring system. |

The mathematical model is given by the following ordinary differential equation: \begin{align} m\ddot{d}+k_{d}\dot{d}+k_{s}d=F \label{eq2:ode} \end{align}

where $d$ is the distance from the equilibrium point, $m$ is the mass, $k_{d}$ and $k_{s}$ are the damping and spring constants, and $F$ is the external force. By introducing the state-space variables $x_{1}=d$ and $x_{2}=\dot{d}$, the model \eqref{eq2:ode} can be written in the state-space form We assume that only the position vector $d$ (that is, the state variable $x_{1}$) can be observed. Consequently, the output equation takes the following form: The state-space model \eqref{state:Mass_spring}-\eqref{output:Mass_spring} of the spring-mass system is in the continuous-time domain. To transform it into the discrete-time domain we use the Backward Euler method. Using this approximation, we obtain: where $h$ is the discretization time step. The last equation leads to

where $\tilde{A}=(I-hA)^{-1}$ and $\tilde{B}=h\tilde{A}B$, and the output equation remains unchanged:

Next, we present a Python code for computing the system response on the basis of the backward Euler method. The code will be used to generate training, validation, and test data for the recurrent neural networks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# define the continuous-time system matrices

A=np.matrix([[0, 1],[- 0.1, -0.05]])

B=np.matrix([[0],[1]])

C=np.matrix([[1, 0]])

#define an initial state for simulation

x0=np.random.rand(2,1)

#define the number of time-samples used for the simulation and the sampling time for the discretization

time=300

sampling=0.5

#define an input sequence for the simulation

#input_seq=np.random.rand(time,1)

input_seq=np.ones(time)

#plt.plot(input_sequence)

# the following function simulates the state-space model using the backward Euler method

# the input parameters are:

# -- A,B,C - continuous time system matrices

# -- initial_state - the initial state of the system

# -- time_steps - the total number of simulation time steps

# -- sampling_perios - the sampling period for the backward Euler discretization

# this function returns the state sequence and the output sequence

# they are stored in the vectors Xd and Yd respectively

def simulate(A,B,C,initial_state,input_sequence, time_steps,sampling_period):

from numpy.linalg import inv

I=np.identity(A.shape[0]) # this is an identity matrix

Ad=inv(I-sampling_period*A)

Bd=Ad*sampling_period*B

Xd=np.zeros(shape=(A.shape[0],time_steps+1))

Yd=np.zeros(shape=(C.shape[0],time_steps+1))

for i in range(0,time_steps):

if i==0:

Xd[:,[i]]=initial_state

Yd[:,[i]]=C*initial_state

x=Ad*initial_state+Bd*input_sequence[i]

else:

Xd[:,[i]]=x

Yd[:,[i]]=C*x

x=Ad*x+Bd*input_sequence[i]

Xd[:,[-1]]=x

Yd[:,[-1]]=C*x

return Xd, Yd

state,output=simulate(A,B,C,x0,input_seq, time ,sampling)

plt.plot(output[0,:])

plt.xlabel('Discrete time instant-k')

plt.ylabel('Position- d')

plt.title('System step response')

Here are a few comments about the code. On lines 6-10 we define the system matrices and the initial condition (a random initial condition).

Lines 13-14: we use 300 time steps, and a discretization step (sampling period) of 0.5 seconds.

Here it should be noted that the discretization step is relatively high, adding additional damping to the system discrete-time system.

Here we do not care about this phenomenon, and we consider the discrete-time system as a data generating system.

On line 18, we define a step function. Uncomment line 17, if you want to use a random signal as an input.

Lines 30-49 define a function that simulates the dynamics and that returns the state and output sequences.

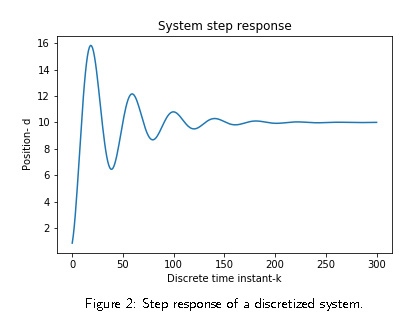

The step response of the system is shown on the following figure.

This is a typical response of an undamped system.

Next, we proceed with training the machine learning models. The following code defines a mass-spring model with arbitrary parameters and defines the discretization steps and the total number of time samples.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

###############################################################################

# Model defintion

###############################################################################

# First, we need to define the system matrices of the state-space model:

# this is a continuous-time model, we will simulate it using the backward Euler method

A=np.matrix([[0, 1],[- 0.1, -0.000001]])

B=np.matrix([[0],[1]])

C=np.matrix([[1, 0]])

#define the number of time samples used for simulation and the discretization step (sampling)

time=200

sampling=0.5

To learn the model, we use a random input sequence. Furthermore, we use a random initial condition. Special care needs to be given to the definition of the training, validation, and test data. According to the Keras documentation, the recurrent neural networks take the tensor input of the following shape: (batch_size, timesteps, input_features). In our case, batch_size=1, timesteps=time+1, and input_features=2. If we denote the test input data by testX, then the entry testX[0,:,:] has the following form

First of all, in order to predict the system response, the model needs to know the initial state. That is why the first row of the above matrix is equal to the initial state. The entries on the first column, starting from the row $2$ to the row $201$ are the input sequence (the force applied to the model). The corresponding entries on the second row are equal to zeros. This has been done in order the sliced tensor dimension constant (Is there a better way to do this?). The output, denoted output_train in the code, is defined in the same manner. The output shape is (1,201,1). The first entry of the sliced output is $x_{01}$ and the remaining entries are equal to the observed output sequence. Here for simplicity, we did not scale the training data. It should be emphasized that the inputs and outputs should not be scaled independently since they are related.

For training, validation and test data we use different initial states and input sequence. That is, for the generated random initial input and initial condition. We simulate the system dynamics. This data is then used to form the input and output tensors. To define the training data, we simulate the system only once. This is done because in practice it is time-consuming to observe the system dynamics for different inputs and initial conditions, and we often can do it only once. The code defining the training, validation, and test datasets is given below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

###############################################################################

# Create the training data

###############################################################################

#define an input sequence for the simulation

input_seq_train=np.random.rand(time,1)

#define an initial state for simulation

x0_train=np.random.rand(2,1)

# here we simulate the dynamics

from backward_euler import simulate

state,output_train=simulate(A,B,C,x0_train,input_seq_train, time ,sampling)

output_train=output_train.T

# this is the output data used for training

output_train=np.reshape(output_train,(1,output_train.shape[0],1))

input_seq_train=np.reshape(input_seq_train,(input_seq_train.shape[0],1))

tmp_train=np.concatenate((input_seq_train, np.zeros(shape=(input_seq_train.shape[0],1))), axis=1)

tmp_train=np.concatenate((x0_train.T,tmp_train), axis=0)

# this is the input data used for training

trainX=np.reshape(tmp_train, (1,tmp_train.shape[0],tmp_train.shape[1]))

###############################################################################

# Create the validation data

###############################################################################

# new random input sequence

input_seq_validate=np.random.rand(time,1)

# new random initial condition

x0_validate=np.random.rand(2,1)

# create a new ouput sequence by simulating the system

state_validate,output_validate=simulate(A,B,C,x0_validate,input_seq_validate, time ,sampling)

output_validate=output_validate.T

# this is the output data used for validation

output_validate=np.reshape(output_validate,(1,output_validate.shape[0],1))

input_seq_validate=np.reshape(input_seq_validate,(input_seq_validate.shape[0],1))

tmp_validate=np.concatenate((input_seq_validate, np.zeros(shape=(input_seq_validate.shape[0],1))), axis=1)

tmp_validate=np.concatenate((x0_validate.T,tmp_validate), axis=0)

# this is the input data used for validation

validateX=np.reshape(tmp_validate, (1,tmp_validate.shape[0],tmp_validate.shape[1]))

###############################################################################

# Create the test data

###############################################################################

# new random input sequence

input_seq_test=np.random.rand(time,1)

# new random initial condition

x0_test=np.random.rand(2,1)

# create a new ouput sequence by simulating the system

state_test,output_test=simulate(A,B,C,x0_test,input_seq_test, time ,sampling)

output_test=output_test.T

# this is the output data used for test

output_test=np.reshape(output_test,(1,output_test.shape[0],1))

input_seq_test=np.reshape(input_seq_test,(input_seq_test.shape[0],1))

tmp_test=np.concatenate((input_seq_test, np.zeros(shape=(input_seq_test.shape[0],1))), axis=1)

tmp_test=np.concatenate((x0_test.T,tmp_test), axis=0)

# this is the input data used for test

testX=np.reshape(tmp_test, (1,tmp_test.shape[0],tmp_test.shape[1]))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Next, we define the networks. We will compare three network arhitectures: SimpleRNN, GRU, and LSTM. For brevity, we do not explain these network arhitectures.

The interested reader is advised to consult the Keras documentation.

###############################################################################

# Here we define the network

###############################################################################

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.layers import GRU

from keras.layers import LSTM

from keras.layers import SimpleRNN

from keras.optimizers import RMSprop

from keras.layers import TimeDistributed

from keras.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

model=Sequential()

#model.add(SimpleRNN(32, input_shape=(trainX.shape[1],trainX.shape[2]),return_sequences=True))

#model.add(GRU(32, input_shape=(trainX.shape[1],trainX.shape[2]),return_sequences=True))

model.add(LSTM(32, input_shape=(trainX.shape[1],trainX.shape[2]),return_sequences=True))

#model.add(Dense(1))

model.add(TimeDistributed(Dense(1))) #there is no difference between this and model.add(Dense(1))...

# does not make sense to use metrics=['acc'], see https://stackoverflow.com/questions/41819457/zero-accuracy-training-a-neural-network-in-keras

model.compile(optimizer=RMSprop(), loss='mean_squared_error', metrics=['mse'])

# after every epoch, we save the model, this is the absolute path on my C: drive, so the path is

# C:\python_files\system_identification\models\

filepath="\\python_files\\system_identification\\models\\weights-{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.6f}.hdf5"

checkpoint = ModelCheckpoint(filepath, monitor='val_loss', verbose=0, save_best_only=False, save_weights_only=False, mode='auto', period=1)

callbacks_list = [checkpoint]

history=model.fit(trainX, output_train , epochs=2000, batch_size=1, callbacks=callbacks_list, validation_data=(validateX,output_validate), verbose=2)

# load the model with the smallest validation loss

#model.load_weights("weights-1997-1.878475.hdf5")

# use the test data to predict the model response

testPredict = model.predict(testX)

A few comments about the code are in order. On lines 15-17, we use the parameter return_sequences=True, because we want that the RNN networks return the state sequence at every time sample (in total we have 201 time samples). Then on lines 26-28 we say to the compiler that we want to store the model (network parameters) after each epoch. The file names are defined according to the validation loss. This has been done in order to retrieve the model with the smallest validation loss. This should be the “best” model, which should be tested on the test data. The commented line 37 loads the model with the best validation loss. On line 40 we use the test data to generate the predicted output, which is then compared with the “true” test output obtained by simulating the original system.

The following code plots the predicted and “true” test data, and plots the training and validation losses with respect to the training epoch number.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

###############################################################################

# Plot the predicted and "true" output and plot training and validation losses

###############################################################################

# plot the predicted and the "true" (test) outputs

time_plot=range(1,time+2)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(time_plot,testPredict[0,:,0], label='Real output')

plt.plot(time_plot,output_test[0,:],'r', label='Predicted output')

plt.xlabel('Discrete time steps')

plt.ylabel('Output')

plt.legend()

plt.savefig('responseLSTM32.png')

plt.show()

loss=history.history['loss']

val_loss=history.history['val_loss']

epochs=range(1,len(loss)+1)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(epochs, loss,'b', label='Training loss')

plt.plot(epochs, val_loss,'r', label='Validation loss')

plt.title('Training and validation losses')

plt.xlabel('Epochs')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.xscale('log')

#plt.yscale('log')

plt.legend()

plt.savefig('lossLSTM32.png')

plt.show()

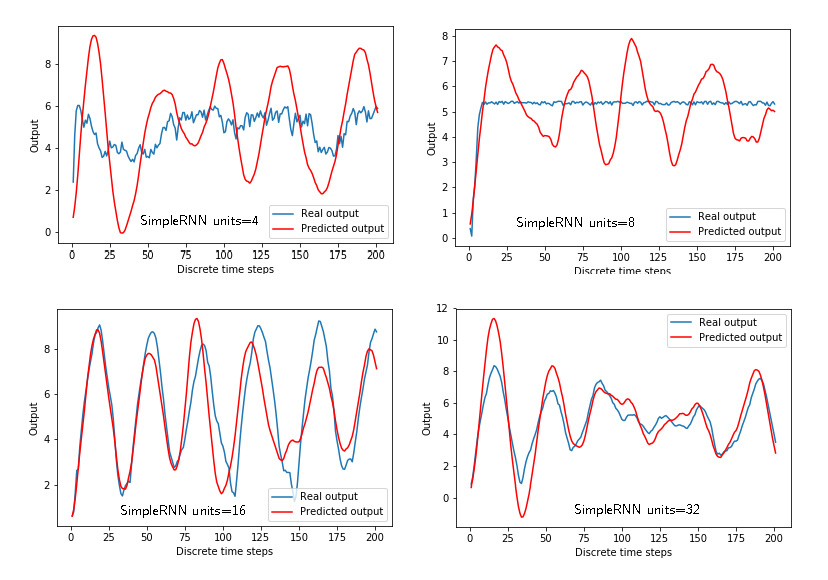

Figures 3 below shows the predicted and “true” outputs for the simpleRNN architecture for different number of units (4,8,16,32). The number of units is the first parameter in the definition of the recurrent layer:

model.add(SimpleRNN(units, input_shape=(trainX.shape[1],trainX.shape[2]),return_sequences=True))

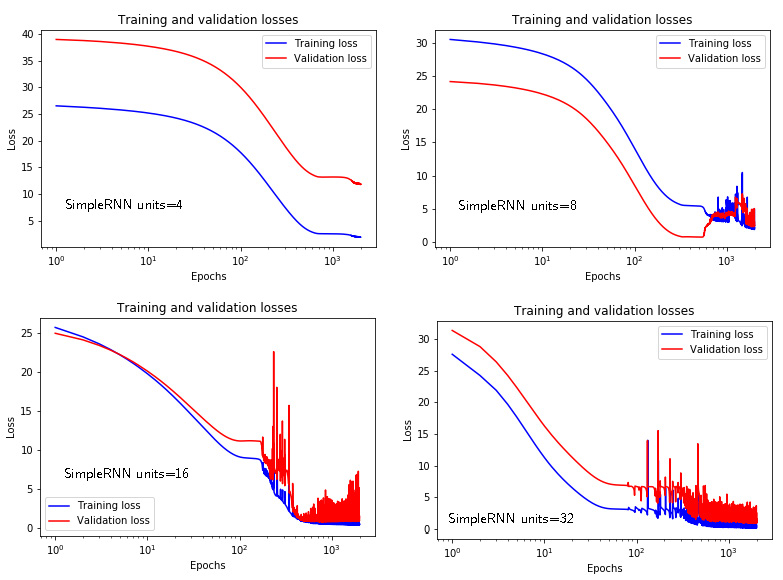

Figures 4 below shows the training and validation losses for the simpleRNN architecture for different number of units (4,8,16,32). The simpleRNN arhitecture with the largest number of units gives the best prediction. Here it should be noted that the training is stopped after 2000 epochs, and the effect of overfitting is not clearly visible.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Predicted and “true” outputs of the simpleRNN arhitecture for different number of units. |

|

|---|

| Figure 4: Training and validation losses of the simpleRNN arhitecture for different number of units. |

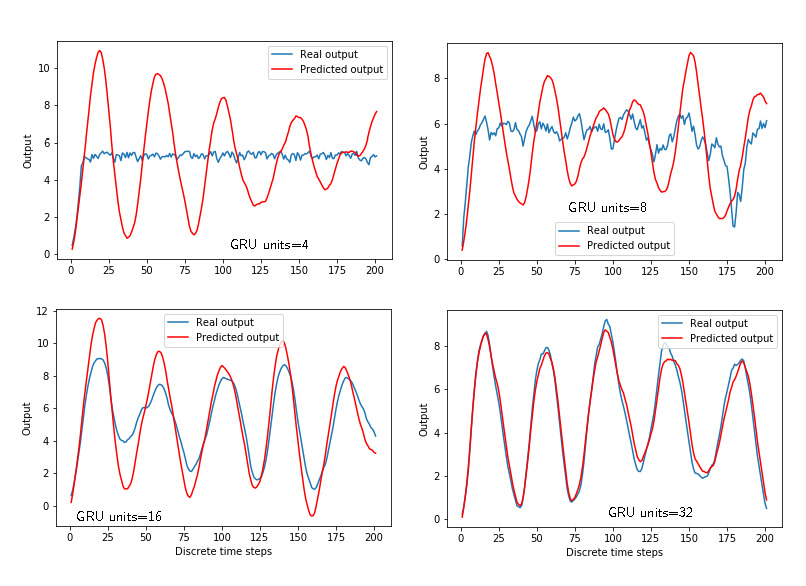

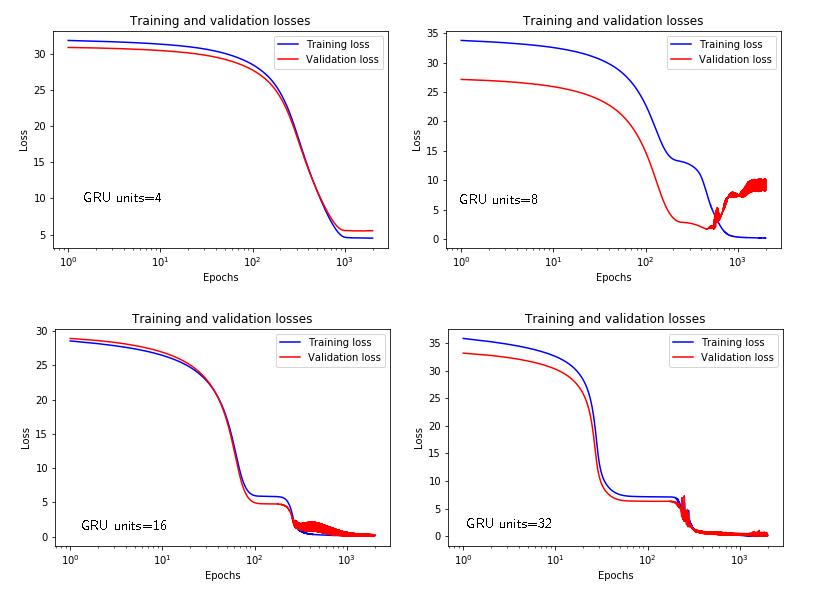

Similarly to Figs. 3 and 4, Figs. 5 and 6 show the time response and losses for the GRU networks with respect to the number of units.

|

|---|

| Figure 5: Predicted and “true” outputs of the GRU arhitecture for different number of units. |

|

|---|

| Figure 6: Training and validation losses of the GRU arhitecture for different number of units. |

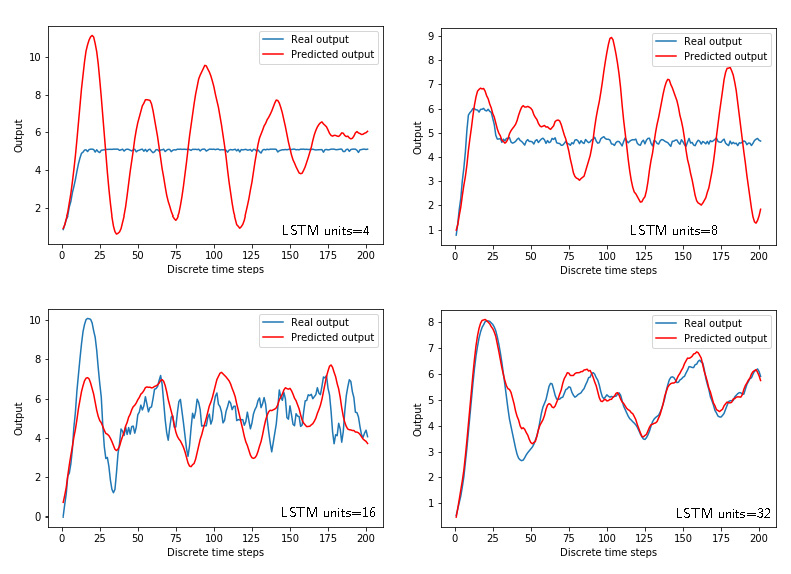

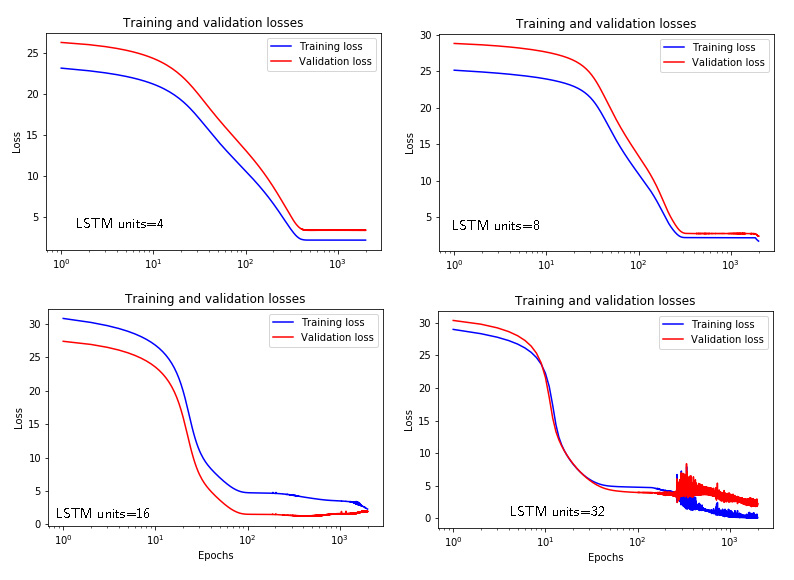

Figures 7 and 8 show the time response and losses for the LSTM networks with respect to the number of units.

|

|---|

| Figure 7: Predicted and “true” outputs of the LSTM arhitecture for different number of units. |

|

|---|

| Figure 8: Training and validation losses of the LSTM arhitecture for different number of units. |